Introduction to Apple Scab

Apple scab is like that unwelcome guest at a party – it shows up uninvited and wreaks havoc. But instead of crashing gatherings, it crashes apple, crabapple, hawthorn, mountain ash, firethorn, and loquat trees. This troublemaker is caused by a fungus called Venturia inaequalis. It thrives in areas with cool, wet spring weather, making itself at home wherever apples are found. While it rarely delivers a knockout blow to trees, it can significantly reduce the quantity and quality of fruit, weakening trees and making them more susceptible to other issues.

Spotting the Signs: How to Identify Apple Scab

Imagine apple scab as a mischievous artist, painting its mark on leaves and fruit. It targets leaves, fruit, stems, and twigs, but its favorite canvas is the fruit and leaves. The fungus spreads in two ways: through primary infection from debris on the ground and secondary infection from spreading over the tree.

On leaves, it begins as small, light yellow-green spots, growing larger and turning olive-green to brown. They develop a slightly fuzzy or velvety texture, resembling a “scab.” Sometimes, leaves deform as the fungus kills some cells, causing the remaining cells to grow around the dead area. Secondary infections may cover entire leaves, creating a “sheet scab.”

On fruit, it starts as brown or green spots, growing into dark brown to black, corky areas. Young fruits may become deformed, and heavily damaged fruit may die and fall from the tree. Even blossoms aren’t safe, with small dark green spots appearing at their base, on sepals, and stems. This can cause resulting fruit to drop prematurely.

Unraveling the Life Cycle of Apple Scab

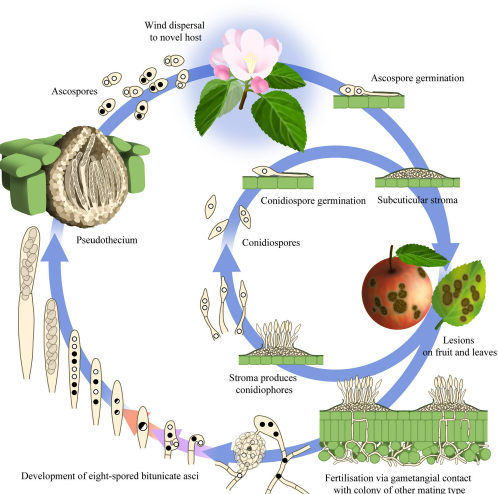

Understanding the life cycle of apple scab is like deciphering a puzzle – each piece revealing the fungus’s cunning strategy. The fungus resides in the outer layers of living plant tissues, patiently waiting for its chance to strike. It finds refuge in dead leaf and fruit debris on the ground during winter.

Come spring, it’s game on. The fungus mates and creates spores, launching them into the air during rainstorms. These spores hitch a ride on the wind and rain, targeting unsuspecting apple trees. This primary infection usually coincides with the blooming of apple trees, and by the time the petals fall, most spores have been launched.

For the spores to germinate successfully, they require about nine hours of continuous wetting at temperatures ranging from 63-75°F. Once they find their target, the spores initiate the primary infection, creating more spores that spread to other leaves or fruit. This secondary infection phase can last from 9 to 30 days, depending on temperature and wetness.

Young leaves and fruit are most susceptible to apple scab. Leaves remain vulnerable until they stop expanding, while fruit is at risk until about three or four weeks after petal fall, albeit to a lesser extent. After this period, the threat diminishes, but it’s not entirely gone until harvest time.

Taking Control: How to Manage Apple Scab

Dealing with apple scab requires a proactive approach, akin to staying one step ahead of a crafty opponent. Here are some strategies to keep it in check:

1. Plant Resistant Varieties: Opt for apple and crabapple varieties that boast resistance to apple scab. This significantly reduces the likelihood of an infestation.

2. Maintain Cleanliness: Keep your orchard tidy by removing dead leaves and fruit from around your trees. This eliminates potential overwintering sites for the fungus, disrupting its life cycle.

3. Manage Irrigation: Avoid splashing water onto leaves and fruit during irrigation. Water during the day, allowing leaves and fruit to dry quickly and reducing the risk of infection.

4. Pruning: Prune your apple trees strategically to enhance sunlight penetration and airflow. This promotes faster drying of leaves and fruit, creating an environment less conducive to fungal growth.

5. Fungicide Treatments: In regions prone to cool, wet spring weather, fungicides may be necessary. A preventative fungicide spray early in the spring, timed to coincide with bud growth until two weeks after petal fall, is highly effective in stopping primary infections. Curative fungicides can be applied as soon as apple scab damage is observed, within 24-96 hours of initial infection, to prevent further damage.

Conclusion

Apple scab may be a formidable opponent, but armed with knowledge and proactive measures, you can keep it at bay. By understanding its life cycle, identifying its signs, and implementing effective management strategies, you can safeguard your orchard and enjoy healthy, bountiful harvests for years to come.